WURZEL SCHLAGEN (Taking Root)

A settlement doesn’t die loudly. It thins out—one closed shutter at a time, one “seasonal” window that never turns into a lived-in light. Wurzel Schlagen is my response to that slow erosion in Feldis: a strategy to restore permanence, invite new life without violence, and let growth behave like an ecosystem—measured, reciprocal, and resilient.

The context: growth that must not become extraction

Feldis sits inside a tension familiar to many alpine villages: a fragile demographic curve, a market pressure toward second homes, and an ecology that carries the settlement’s identity more faithfully than any postcard façade. The municipal designation of buildable parcels—paired with the requirement that specific plots become primary residences within a defined period—is not merely regulation; it is a moral prompt. It asks: If you own land here, will you also participate in the life of this place?

My proposal accepts that prompt and turns it into an architecture of commitment: soft densification that strengthens the existing narrative rather than overwriting it; housing that makes year-round life possible; and public space that re-teaches people how to meet again.

Five principles, one ethos: continuity by intelligence

I did not approach Feldis as a museum. I approached it as a living grammar.

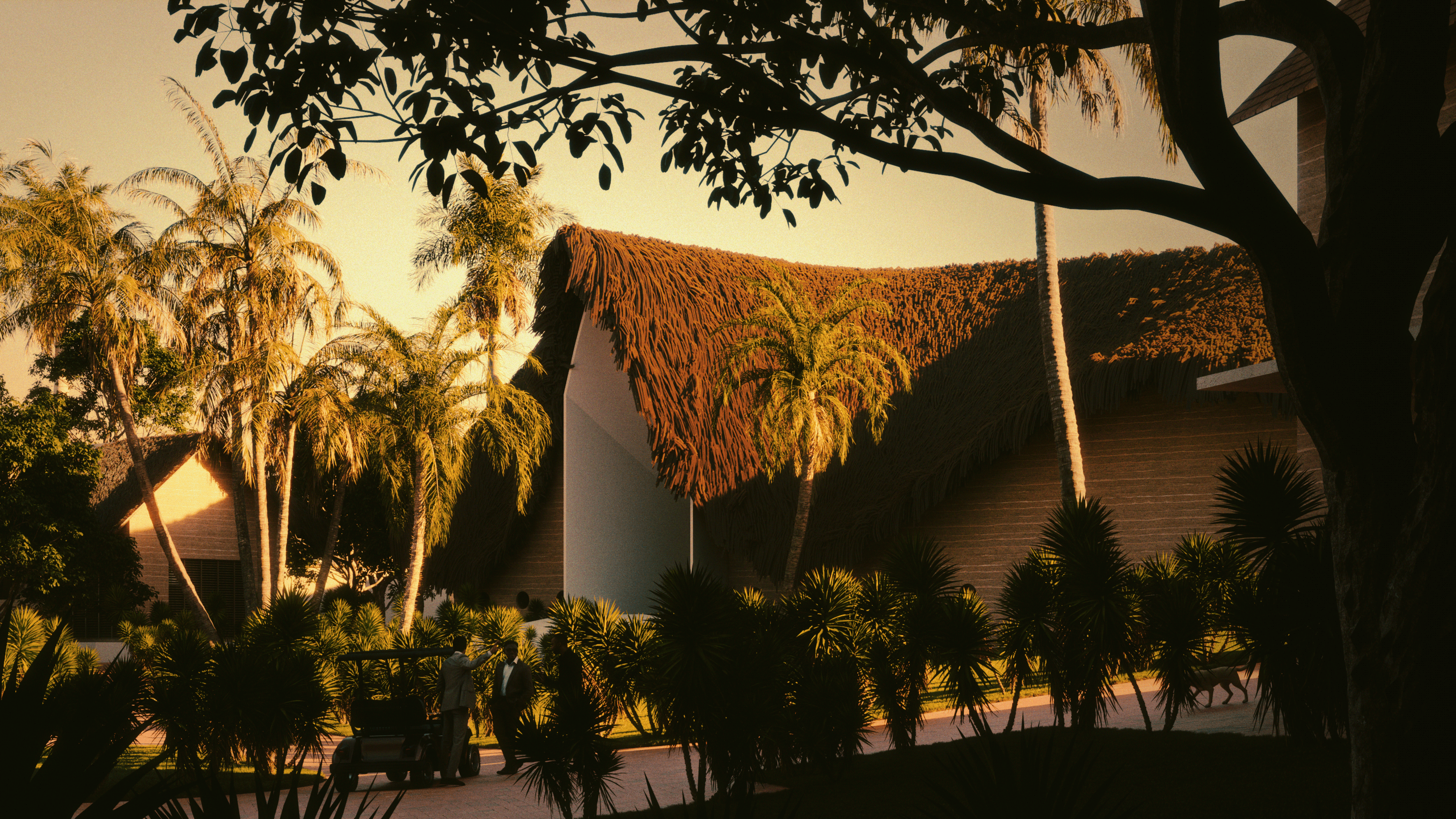

1) Preserved built heritage: continuation by principle

The work begins with respect—not nostalgia. The goal is not to “copy” old Feldis, but to continue its logic: roof pitches that belong to snow and wind, stone bases that feel inevitable against the earth, fenestration rhythms that understand scale and privacy. New buildings complete an unfinished sentence rather than speaking over it.

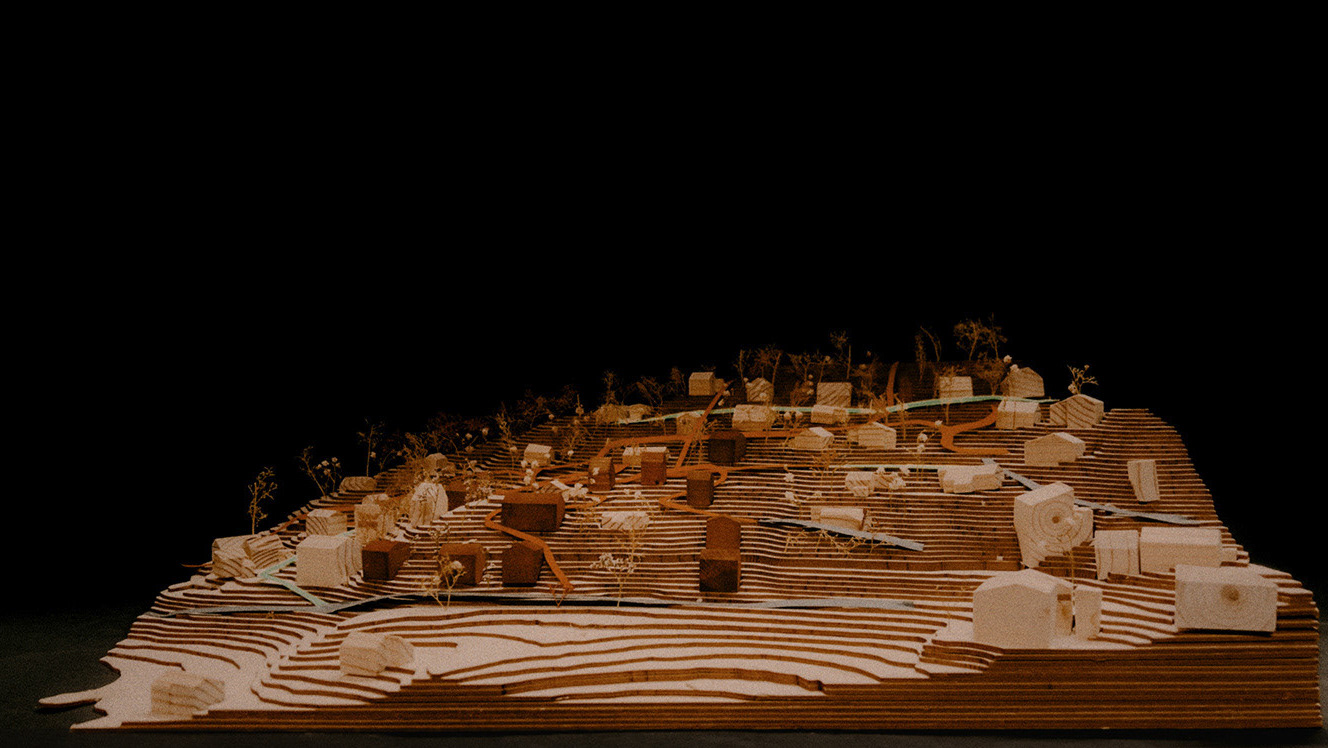

2) Regulated densification: permanence without rupture

Densification here is not vertical dominance; it is careful multiplication. I propose owner-occupier mixed-use models that increase capacity while preserving the village’s roofline discipline and landscape legibility. This is not expansion for spectacle—it is growth as repair: adding homes specifically for year-round residency, countering vacancy, and widening the demographic base to include younger households and multi-generational living.

3) Social cohesion: weaving the new to the old

The Vazzal must not become a detached neighborhood. It must be stitched into Feldis—physically and socially—through paths, pauses, and shared programs that pull people into contact without forcing performance. I treat public space as a civic instrument: not decorative paving, but a choreography of encounter.

4) Spatial connectivity: a “Treaty of Movement”

Movement is never neutral: it either divides, or it composes. I reimagine key routes as hybrid corridors where vehicle access, pedestrian comfort, and ecological performance coexist. The street edge becomes permeable; water is invited to seep rather than flee; planting is not garnish but infrastructural softness. In this treaty, the pedestrian is honored—through texture, verge ecology, and moments that turn “getting there” into “being here.”

5) Ecology as infrastructure: architecture as an extension of the ecosystem

I refuse the shallow sustainability of mitigation-only thinking. Here, ecology is treated as a core utility—as essential as a road or a roof. Wildflower meadows, orchards, habitat belts, and constructed wetlands are not amenities: they manage stormwater, cool microclimates, support pollinators, and give the village an education written in living matter. The settlement’s edges become productive and restorative landscapes—places where stewardship becomes daily habit, not occasional ideology.

What success looks like:

Success is not measured only in unit counts or diagrams. Success is:

1. a village where lights return in winter, not just summer;

2. a street where rainwater is treated as a guest, not a problem;

3. orchards and tree canopies that feeds both pollinators and people;

4. a bench that becomes a ritual;

5. and a new generation that can afford to take root without being forced to leave its future elsewhere

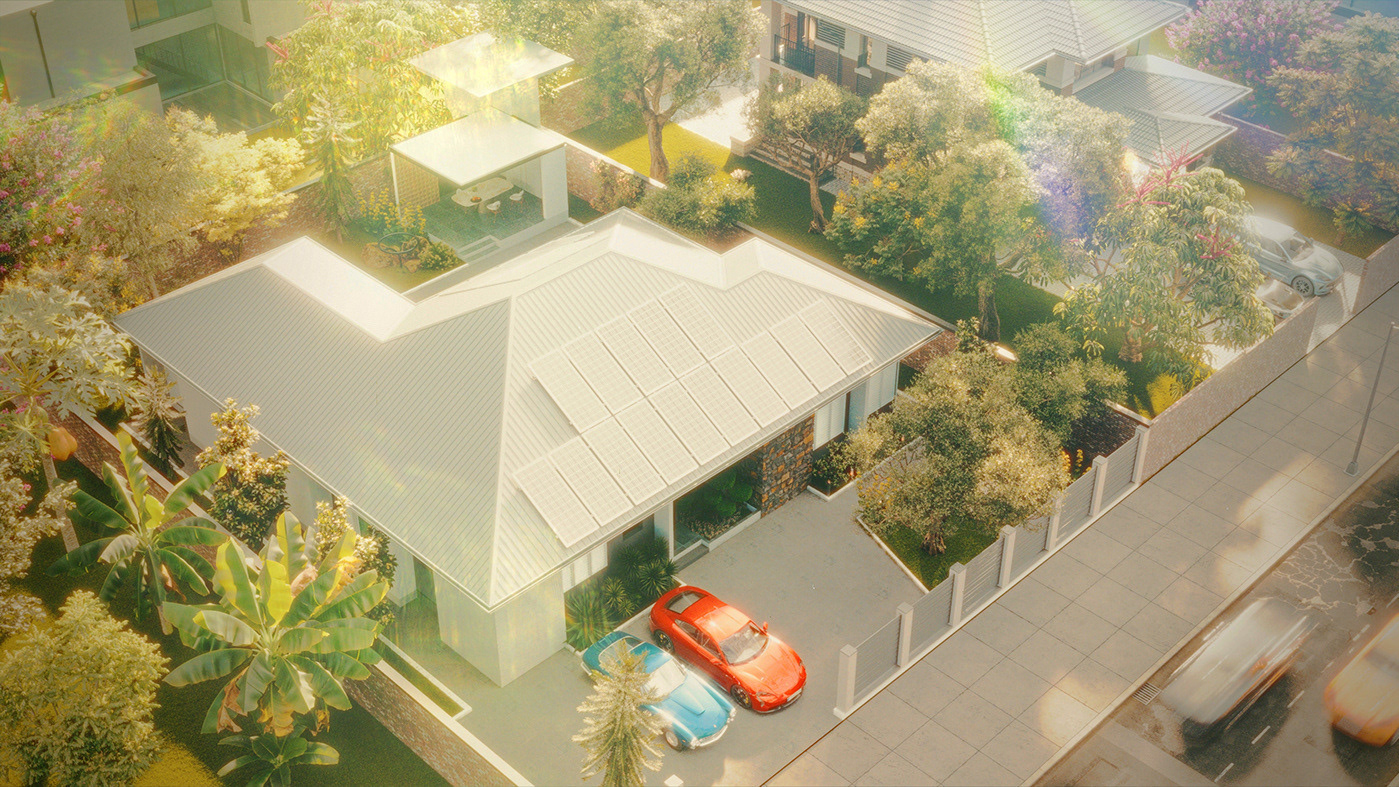

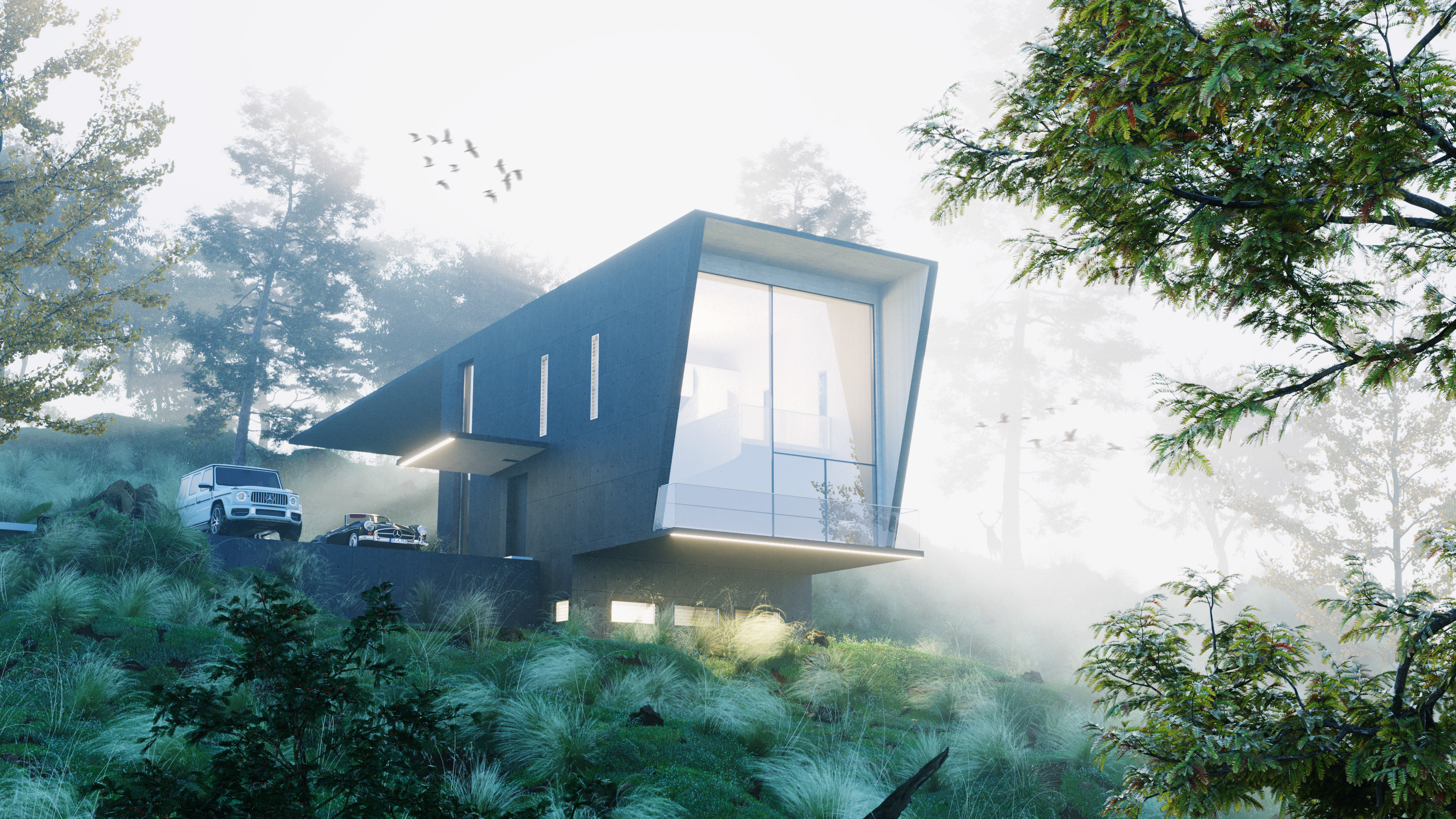

The housing prototype: the building as a civic contract

At the architectural scale, the proposal crystallizes into an owner-anchored, multi-family typology designed to do something quietly radical: make permanence desirable and feasible.

Owner-occupier at the top: stewardship is not abstract; it has a face and a daily presence.

Rental units below for primary residents: the building becomes a vehicle for demographic renewal, not speculative yield.

Mixed-use at ground level (where appropriate): small-scale program can catalyze social life—spaces that support a community kitchen, workshop culture, or local services, depending on site adjacency and need.

The envelope is conceived as the building’s conscience: rooted in the local material lexicon, climatically intelligent, and quietly contemporary. Thickened edges, deep-set openings, and a massing discipline calibrated to Feldis’ silhouette allow the building to feel inevitable—as if it has always belonged, even while clearly speaking in today’s voice.

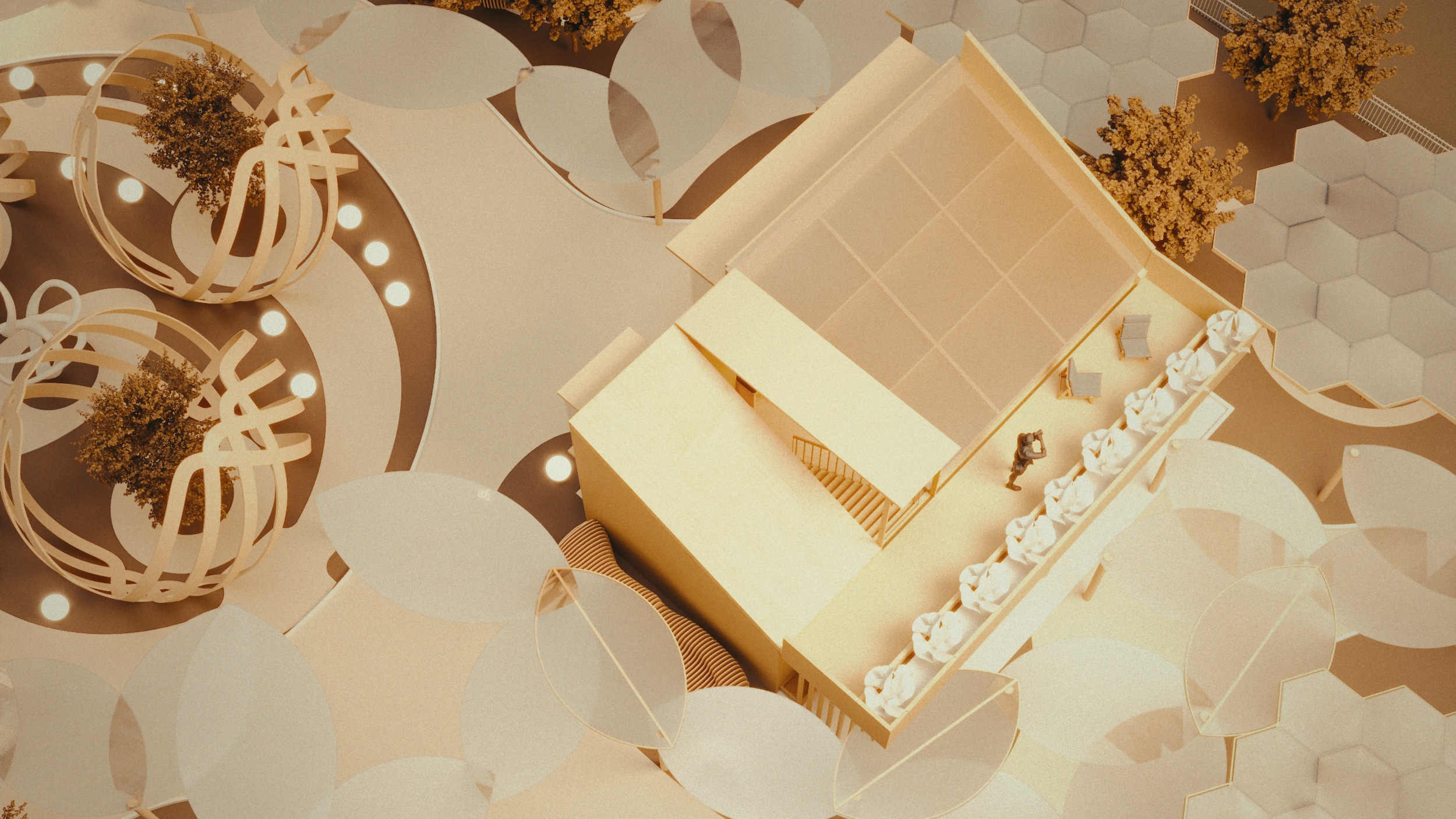

“Stations for Regarding”: public hearths for a village that wants to meet again

A healthy settlement needs more than housing; it needs third places—small, dignified settings where people can pause without paying for the right to exist. I introduce a curated network of benches and gathering nodes as Stations for Regarding: orchestrated pauses that frame views, slow movement, and allow spontaneous conversation to feel natural again. This is how social fabric is repaired—not through grand plazas, but through precise kindness.

Trails and the wider landscape: making the forest part of daily life

West of the Vazzal lies a forest with the capacity to become Feldis’ everyday sanctuary: walkable and bikeable scenic routes, connected to lookout plateaus and panoramic clearings. By activating these trails, the project extends beyond “settlement improvement” into a larger promise: that well-being is not a luxury, but an accessible rhythm—minutes away from one’s front door